Protecting Bunyip Birds, Brolgas Vital to Indigenous Culture

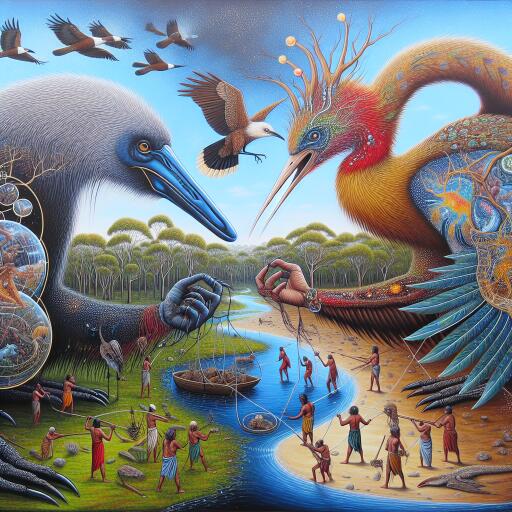

In the vast territories of Kamilaroi Country, which stretches beyond Tamworth into the reaches of northwestern New South Wales and over into Queensland, the landscape pulses with stories and spirits honed over millennia. This is a domain where the Australasian bittern—revered as the bunyip bird—and the brolga, known in Kamilaroi as burraalga, are not just birds but intrinsic elements of the Indigenous culture, lore, and spiritual life.

Yet, in this revered Country, the reverence shown to these creatures by the Kamilaroi people contrasts sharply with their current reality. Once abundant, both species are now facing the risk of fading from the lands that have echoed their calls for thousands of generations. The Kamilaroi community is determined to reverse this decline, but their efforts brush up against a significant hurdle: the gap between Western conservation laws and the protection of species that are culturally significant.

Western conservation approaches typically assess the threat level to a species based on its numbers and distribution. A species is deemed threatened if it is at risk of not recovering due to declining population or habitat. Accordingly, legal protections and recovery funding are mobilized to safeguard these species. However, this method focuses primarily on quantifiable aspects of nature, sidelining the intricate interplay between nature and culture that is pivotal in Indigenous perspectives.

This divergence points to a deeper issue regarding whose environmental research and management strategies are validated and funded, and how knowledge is exchanged and shared. Bridging this gap is essential for aligning ecological conservation efforts with Indigenous cultural preservation, an alignment that is especially pertinent as Australia contemplates a comprehensive overhaul of its nature conservation laws.

The Gwydir wetlands, a sacrosanct site within Kamilaroi Country, encapsulates this intersection of ecological and cultural vitality. It used to teem with brolgas and bunyip birds. The brolga, celebrated for its intricate mating dances, symbolizes critical cultural motifs through its embodiment in local dance. Yet, sightings of these majestic birds have dwindled, not just in Kamilaroi wetlands but across southern Australia.

Similarly, encounters with the elusive bunyip bird, whose distinct cry is entwined with ancestral lore, warning of the sacred and dangerous waterholes guarded by the mythical bunyip, have become increasingly rare. These stories and the connectedness they signify are elemental to Kamilaroi identity, embedding the brolga and bunyip bird deeply within the fabric of their culture and existence.

Despite their vulnerable and endangered status in New South Wales and the near presence to Kamilaroi Country, current conservation policies do little to facilitate Kamilaroi access to, or management of, these species’ habitats. The challenge intensifies for culturally significant species that, while generally abundant, face localized threats and have diminished ranges. This inadequacy highlights the limitations of government conservation programs in addressing the needs of Indigenous communities and protecting species pivotal to their cultural heritage.

The push for a more inclusive approach in ecology is gaining momentum, one that respects and integrates Indigenous knowledge into conservation practices, champions co-management, and appreciates the inseparable bond between people and nature. Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices offer invaluable insights and methodologies for ecological management, far beyond what is currently acknowledged within Western frameworks.

What if conservation policies and practices were reimagined to embrace this holistic view, recognizing the indivisible connection between nature and culture? Such an approach would prioritize Indigenous governance and knowledge systems, permit Indigenous people to define their conservation goals and success measures, and ensure that their voices lead the efforts to sustain the intertwined destinies of species like the brolga and bunyip bird within their ancestral lands.

When a brolga descends onto the Gwydir Wetlands to perform its heralded dance, it’s not merely an ecological event but a manifestation of the world’s oldest living culture continuing its ancestral stewardship. This spectacle isn’t just about a bird species striving to thrive; it’s a testament to the enduring bond between the Kamilaroi people and the natural world, a relationship that, if nurtured, promises to enrich both ecological outcomes and cultural continuity.

Leave a Reply