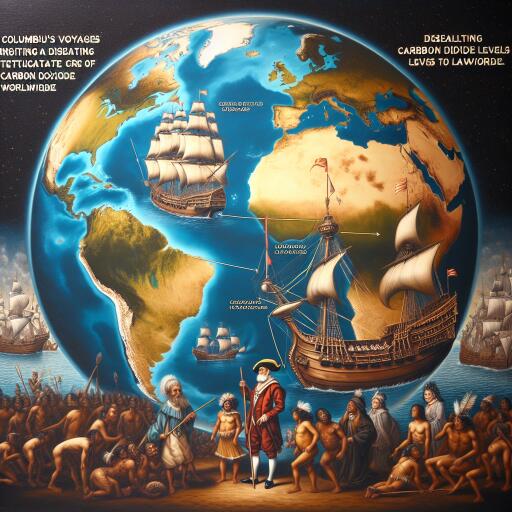

Columbus’ Expeditions and their Unintended Impact on Global Climate

In 1492, Christopher Columbus set sail across the Atlantic, a voyage that not only opened up new routes of exploration and exploitation but unwittingly heralded a significant shift in the Earth’s climatic history. The arrival of European settlers in the Americas initiated a series of events that had catastrophic implications, not just for the indigenous populations but, intriguingly, for the global environment as well.

The tragic tale often untold is that of the colossal demographic collapse among the Americas’ native populations due to diseases brought by Europeans. Lacking immunity to smallpox, influenza, and other foreign pathogens, an estimated 80% to 95% of the Indigenous people perished within 150 years post-contact. From a flourishing civilization numbering in millions, the population dwindled to less than 500, marking a stark era of loss and devastation.

Beyond the human tragedy, this massive depopulation had unexpected consequences for the planet’s climate. A fascinating discovery was made through the study of ice cores — long columns extracted from ice caps and glaciers, which serve as historical records by trapping air bubbles from different epochs. These trapped bubbles revealed a notable decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels during the 16th and 17th centuries, coinciding with the aftermath of Columbus’ expeditions.

The explanation for this sudden drop in CO2 levels lies in the vast tracts of agricultural lands that were abandoned as the native population declined. These lands, once cleared and cultivated, began to be reclaimed by forests and other vegetation, which, through photosynthesis, absorbed significant amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It is estimated that around seven billion metric tons of carbon were sequestered as a result of this regrowth of the American forests. This marked change in terrestrial carbon uptake was significant enough to leave a discernible mark on the global atmospheric composition.

Analyses of ice core samples provided further insights into this phenomenon. Two specific ice cores — the Law Dome core and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) core — have been central to our understanding of atmospheric conditions over the past two millennia. While both cores evidenced the decline in CO2 levels during the period of interest, the Law Dome core presented a steeper decline compared to WAIS, aligning with models that suggest a considerable reorganisation of land use following the Europe-Americas encounter.

This historical linkage between human activity and climate change presents an early instance of a large-scale human-driven alteration in the Earth’s climate, distinct from the primarily warming trends associated with human activities today. The analysis of ancient climates, especially through the lens of ice core research, emphasizes the intricate connections between human history and climatic shifts. Moreover, it underlines a less frequently observed facet of human influence — global cooling, provoked not by technological advancement or industrial emissions but by tragic circumstances that led to a significant rewilding of once-cultivated lands.

As such, the story of Columbus and the subsequent European conquests, often narrated for their historical and cultural ramifications, also stands as a profound reminder of the complex interplay between human societies and the Earth’s climatic systems. It underscores the undeniable truth that human activities, whether through conquest, colonization, or industrial growth, have long been powerful enough to sway the delicate balance of our planet’s climate.

Leave a Reply