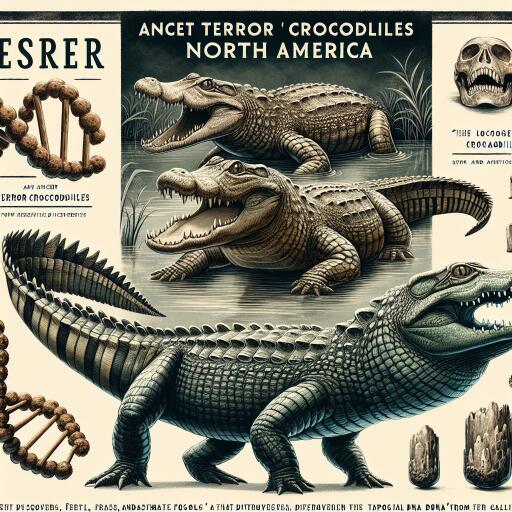

The Ancient ‘Terror Crocodiles’ of North America Weren’t Alligators After All, DNA and Fossils Suggest

Over 75 million years ago, a colossal reptilian predator roamed the waters of what is now North America. Known as the “terror crocodile,” this creature, called Deinosuchus, was long thought to be closely related to modern alligators. However, new research challenges this assumption, positioning Deinosuchus quite differently on the crocodilian family tree.

A research team conducted an extensive analysis of DNA and fossils from 128 species, both living and extinct, that belong to the crocodilian group—crocodiles, alligators, and caimans—providing insights into their evolutionary history. Their findings, recently published, suggest that Deinosuchus was more akin to modern crocodiles than alligators, particularly in its ability to tolerate saltwater environments.

The study further reveals that gigantic crocodilian species, like Deinosuchus, may have evolved more frequently than previously thought. For instance, the giant caiman Purussaurus from South America was known to grow to a length double that of a typical pickup truck, and Sarcosuchus patrolled regions that are now South America and Africa.

“It seems that having giant crocs at a given time was almost a norm,” notes a paleontologist involved in the study. “Giant crocodilians weren’t uncommon during various eras.”

In the Cretaceous period of North America, Deinosuchus was particularly remarkable. As a dominant predator, it had a massive appetite and would prey on virtually anything, including dinosaurs. This fearsome creature captured its victims with teeth the size of bananas.

These massive predators thrived thanks in part to a unique adaptation—a tolerance for saltwater. During the Cretaceous, the Western Interior Seaway divided North America into two separate landmasses, and fossils of Deinosuchus have been discovered on both sides of this seaway, leaving researchers puzzled. Unlike modern alligators, which prefer freshwater environments, how did Deinosuchus manage to traverse this salty divide?

The answer may lie in Deinosuchus not being an alligator at all. This ancient predator likely possessed salt glands that enabled it to survive in saltwater, allowing it to cross the sea and flourish in coastal areas teeming with large prey, helping it grow to such formidable sizes.

This ecological flexibility might have been crucial for crocodilian species facing environmental changes, such as sea-level rise, which could have exterminated less adaptable species.

The research team’s reconstruction of the crocodilian family tree proposes that Deinosuchus branched off before the last common ancestor of today’s alligators and crocodiles, giving it characteristics of both lineages. The salt tolerance seen in Deinosuchus could have been a trait lost in alligators but retained in modern crocodiles.

“Our new understanding of Deinosuchus’ place within the family tree means that their ancestors’ capacity for saltwater tolerance has likely been preserved in this genus,” suggests the study’s lead author. “While not marine creatures themselves, Deinosuchus crocodiles might have been capable of crossing the Western Interior Seaway, enabling them to proliferate.”

Despite these intriguing findings, some researchers remain skeptical. There are suggestions that Deinosuchus might not have regularly inhabited saltwater but rather ventured into salty seas only when necessary. Skeptics cite the existence of different species on either side of the seaway as evidence that frequent crossings may not have occurred, proposing that any crossing event might have been singular or rare.

Nevertheless, other experts hail the study as fitting neatly into the broader understanding of crocodilian ecological flexibility, both extinct and extant. The research illuminates much about the evolutionary and ecological significance of this extraordinary prehistoric croc.

Leave a Reply