Mapping Mercury Contamination in Penguins of the Southern Ocean

Six decades after the infamous DDT contamination crisis, researchers are turning their attention to another global environmental pollutant. This time, the pollutant in question is mercury, and the indicators are penguins residing in the remote expanses of the Antarctic Peninsula. Mercury, akin to DDT, has been discovered in locations distant from direct human sources, underscoring the pollutant’s far-reaching influence due to atmospheric transportation.

Mercury, a hazardous neurotoxin, has the capability to bioaccumulate in both aquatic and terrestrial food sources, with fish-eating creatures facing the greatest contamination risk. Prolonged exposure to mercury can affect reproductive functions and induce neurological disorders, such as lethargy and weakness, proving fatal in substantial doses.

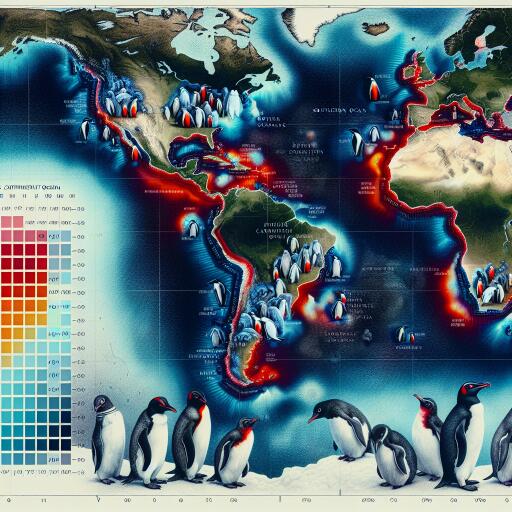

In a recent study, researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis of adult penguin feathers gathered from a breeding site near Anvers Island in the West Antarctic Peninsula. Feathers from three different penguin species—Adelie, gentoo, and chinstrap—were sampled. In addition to examining mercury levels, the researchers investigated the proportions of carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 isotopes in the samples. Carbon-13 serves as a tracer of foraging locations, while nitrogen-15 indicates the food chain positions. These markers facilitated the identification of mercury sources affecting penguins across the Southern Ocean.

The research findings revealed significant variations in mercury accumulation among the penguin species. Adelie and gentoo penguins displayed some of the lowest mercury levels compared to any other penguin species observed to date in the Southern Ocean. In contrast, chinstrap penguins exhibited notably higher mercury levels. This variation is attributed to difference in feeding patterns. During the nonbreeding winter season, chinstraps migrate to lower latitudes farther north, where they encounter higher mercury concentrations compared to penguins residing further south. This relationship is notably evidenced by the strong correlation between foraging locations (carbon-13) and mercury levels in penguin feathers.

The granular insights provided by these findings significantly contribute to the worldwide effort of documenting mercury pollution in marine animals. Previously unknown, it’s now clear that penguins migrating northward face higher mercury exposures. Such data not only illuminate mercury accumulation but also offer a broader understanding of penguin ecology.

While the sources of mercury contamination have evolved over recent decades, airborne mercury historically entered the atmosphere as a byproduct from coal-fired power plants. Due to initiatives aimed at curtailing mercury pollution, particularly following the 2013 adoption of the Minamata Convention on Mercury by numerous countries, releases of mercury into the environment have been reduced. A notable decline in atmospheric mercury levels, approximately 10% between 2005 and 2020, can be attributed to the reduction of coal-fired power plants.

However, mercury pollution continues to arise from alternative sources, such as small-scale gold mining in developing nations. During these mining activities, elemental mercury is used to extract gold from ore, leading to substantial amounts of mercury waste being released into the environment.

The study underscores how feeding patterns impact penguin health and how mercury circulates within the global oceans. Present-day efforts mirror the scientific community’s vigilance from the 1960s in monitoring DDT. There is a hopeful anticipation of observing a decrease in mercury levels among fish, which are crucial both to marine animals and human populations. While the path is long, each finding adds a piece to the larger puzzle of understanding and mitigating mercury contamination across the globe.

Leave a Reply