Indian Firms Are Mining E-Waste for Battery Minerals – But Must Pay More Heed to Waste Collectors

Urban mining presents a significant opportunity for India to bolster its supply of vital minerals, essential to fuel the nation’s burgeoning market for electric vehicles (EVs), including scooters, bikes, and three-wheelers.

Each morning before dawn, Mohammad Abrar wakes in a haze of coughing, a consequence of the dense smog that blankets New Delhi. By 4 am, Abrar, aged 50, reaches the bustling e-waste hub of Seelampur, located in the north-eastern suburbs of the capital, renowned as India’s largest electrical-waste market.

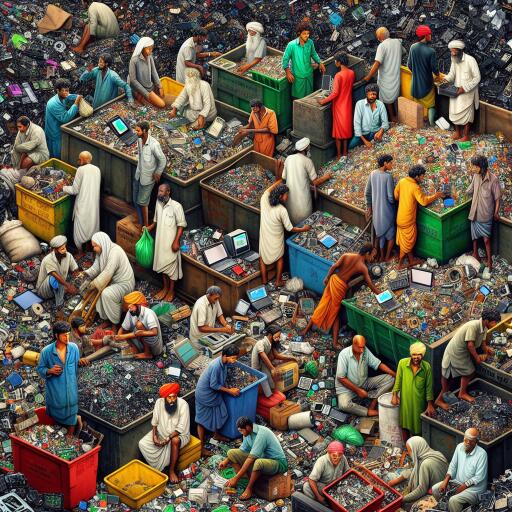

Here, amidst narrow overcrowded lanes, small scrap stores overflow with discarded electronic items—computers, telephones, TVs, and an array of outdated batteries waiting to be disassembled. Abrar is among the vast network of over 50,000 informal workers, including many women and children, whose livelihoods depend on extracting valuable materials from these streams of e-waste.

In recent years, these workers have formed the backbone of a growing sector of start-ups focused on extracting critical minerals from e-waste—an initiative often termed “urban mining”. Amidst the troves of discarded electronics in Seelampur lies a goldmine for the minerals essential to global clean energy transitions.

Copper, found in everyday charging cables, is a key component in electricity-related technologies, while aluminium from electronic devices is crucial for solar panel production. Batteries, however, remain the most coveted. Lithium, cobalt, and nickel—found in mobile devices, laptops, and other electronics—are essential for manufacturing EV batteries and renewable energy storage solutions.

Abrar collects e-waste meticulously, selling his gleanings to traders who then pass them on to recycling companies eager to access this largely untapped reservoir of transition minerals. The task is laborious and perilous, often for little remuneration.

Workers dismantle electronic gadgets and batteries using basic tools and heat to extract metals, creating toxic fumes that give the area its infamous “toxic sink” nickname. The hazardous environment exposes workers to pollutants that carry dire health risks, including lung cancer and organ damage, while vulnerable groups face increased dangers of neurological disorders and other critical health issues.

Despite these risks, Abrar works without fundamental protective equipment, motivated by the necessity of providing for his family. “I must do this for my family. The more waste I deliver, the more I earn,” he admits.

Enter Metastable Materials, a start-up capitalizing on the untapped potential of e-waste. Based in Bengaluru and supported by key Indian investors, the company extracts lithium-ion batteries from discarded electronics to recover valuable minerals for new battery production. This company represents the forefront of a nascent industry projected to grow India’s e-waste recycling market to $7.5 billion by 2030.

Recycling presents a pathway to meet burgeoning clean energy demands with reduced ecological and social repercussions compared to traditional mining. Estimates from global energy authorities suggest significant reductions in the need for new mining could be achieved through recycling efforts, while offering a marked decrease in carbon emissions.

Metastable uses an innovative, cost-effective, and eco-conscious process for recycling lithium-ion batteries, avoiding the use of harsh chemicals and conserving energy. Operating from a modest facility on the city’s periphery, the company maintains a commitment to environmentally-friendly metal extraction processes aimed at supporting the EV market transition.

Despite intentions to revolutionize e-waste management, the industry still heavily relies on informal workers like Abrar, whose earnings barely provide a subsistence living, lacking any form of safety net or social protection.

Industry experts advocate for the formalization of these workers within the recycling supply chain. Ensuring fair compensation and health benefits is crucial as recycling companies expand their operations.

The Indian government has laid plans to substantially increase the country’s recycling capabilities, targeting high recovery rates for EV battery materials by the end of the decade. Initiatives supporting research, along with forthcoming regulatory frameworks, aim to create a robust recycling and urban mining ecosystem.

With global urban mining efforts lagging, India’s strategy could serve as a model for bridging the critical mineral supply gap sustainably. However, these plans hinge significantly on properly integrating and compensating informal workers who play an essential role in the supply chain.

As India navigates the complexities of e-waste management, it must address the need for equitable treatment of its worker base, a challenge that remains pressing amidst rapidly advancing clean energy ambitions.

Leave a Reply